Hier is een artikel van de JapanTimes met de uitleg over Japanse data op voedsel verpakkingen:

Can I eat this? What's the difference between '消費期限' (shōhi kigen) and '賞味期限' (shōmi kigen)?.

Expiry dates

Dear Alice,

My teenage daughter recently turned into a food-label tyrant, apparently convinced that her doddering old parents aren’t up to the job of maintaining a safe kitchen. She patrols our refrigerator daily, fiercely checking every label. If the date on a package has passed, she tosses it in the trash. We’ve had fights about this. I’ve explained that manufacturers set those dates conservatively, so food is still safe to eat for a while past expiry. She insists we’ll die if it’s even one day over. So, what’s the truth? What the heck do those dates really mean?

Sam T., Kumamoto

Dear Sam,

It’s hard when our children decide we’re past our prime, but old dogs can learn new tricks. Let’s prove we’ve still got a little shelf life by sorting out an admittedly tricky subject.

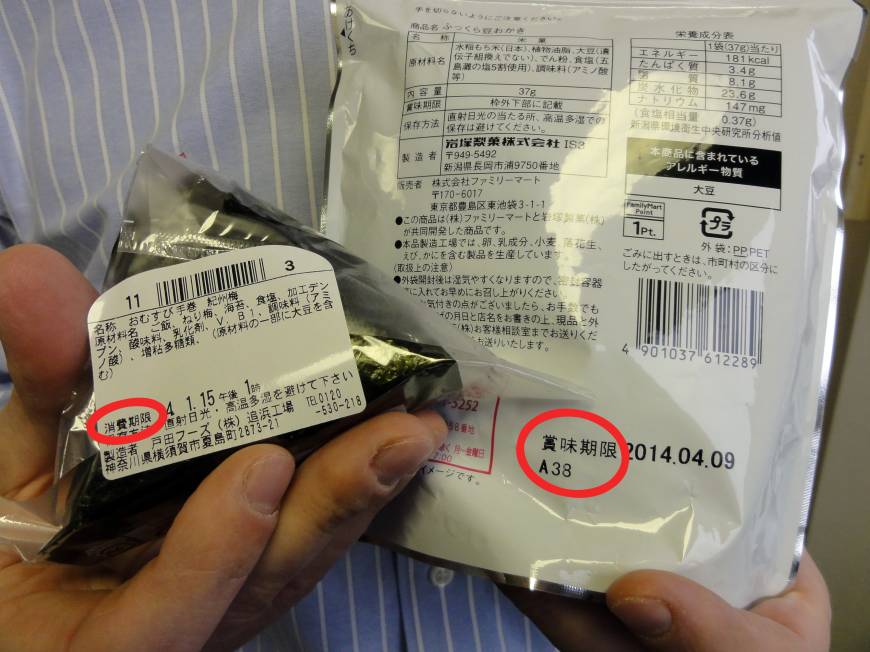

First of all, there are two distinct types of dates used on food packages in Japan: shōhi kigen (消費期限) and shōmi kigen (賞味期限), which mean different things and are used on different foods. The two look confusingly similar in roman letters but are a little easier to distinguish when written in Japanese. For reference, both are visible in the photograph accompanying today’s column.

I started my research at the Consumer Affairs Agency in Tokyo, where officials were sympathetic about your troubles. “Date labeling is confusing for Japanese consumers, too,” one assured me. “Many people don’t understand the difference between shōhi kigen and shōmi kigen, and they don’t know how to use the information.”

That’s partially because the system is relatively new. Until 1995, companies were required to label foods with the date of manufacture. But consumers had no way of knowing how long after manufacture a product was safe to consume, and a lot of perfectly good product was returned or discarded. The current labeling was adopted to address that problem and to bring Japan’s labeling into line with international standards. Now, as part of an effort to reduce shokuhin rosu (food loss), various government agencies are making a renewed effort to help consumers use date-labeling correctly.

Let’s do our part by learning the terms, starting with “shōhi kigen,” which you can see on the rice ball in the left side of the photo. It’s the four characters in front of the date. It means “limit for consumption” and is equivalent to the “use by” wording on food labels in English. “Shōhi kigen” is used for highly perishable products, including bento box meals, sandwiches and cakes made with fresh whipped cream

A shōhi kigen should be taken seriously, because any product that warrants this labeling goes bad quickly after its “use by” date. The government states it this way: “Kigen ga sugitara, tabenai hōga yoi.” (“If the date has passed, it’s better not to eat it.”) Adjusting for the less forceful way of expressing things in Japanese, they’re telling you to pitch it.

Now look at the four characters on the snack package on the right in the photo. They read “shōmi kigen,” which corresponds to “best by” and “best consumed by” in English. The government defines “shōmi kigen” as, “Oishiku taberu koto ga dekiru kigen” (“The limit for best taste”) adding, “Kono kigen o sugitemo sugu taberarenai toiu koto wa arimasen.” (“That doesn’t mean the product can no longer be eaten as soon as the date has passed.”) This labeling is used on products with a long shelf life, including potato chips, instant noodles and canned food. Here, the date is more a reference to quality than safety. You might find the flavor off in out-of-date product, and the nutritional value may not be what it once was, but you’re unlikely to come to any harm if you consume it.

But be aware that there are also moderately perishable foods, including milk, eggs, ham and tofu, that are labeled with shōmi kigen (“best by”) rather than shōhi kigen (“use by”). All these products are safe to eat for some days after the date on the package. It’s difficult to say exactly how long, but fortunately it’s pretty obvious when one of these foods goes bad. The government advises you to rely on your senses, checking for off colors and smells, and even taking a little into your mouth to make sure it’s right.

You are absolutely correct that manufacturers set their “best by/use by” dates conservatively. In fact, government guidelines tell them to do so. The industry term for this is “anzen keisū,” which is expressed as “factor of safety” in English. The guidelines don’t specify what factor of safety should be used, but most food manufacturers in Japan use a 0.8 or 0.7 factor of safety.

Here’s how that works, using an example I found on an industry website. If, for example, testing on a product shows that bacterial levels are within safe limits even five days after the date of manufacture, a company may use a 0.8 factor of safety (five days × 0.8 = four days) to set the shōhi kigen at four days.

Throwing out good food is not only hard on your pocketbook, it’s also bad for the environment and a shame when so many people in the world are hungry. And given that Japan depends on imports for 60 percent of its food, it could be dangerous in times of crisis. Nevertheless, every year Japan produces more than 18 million tons of food waste, much of which is believed to still be edible. Some of this waste originates in industry practices, but an estimated half comes from households who buy more than they need and throw out food that is still safe to eat.

So, is this enough information to convince your daughter to relax her guard? I do hope she’ll work with you to strike a balance between safety and the wise use of food. And maybe she won’t put you out to pasture just yet.